Life Course Translational Research Network

A nationwide network of thought leaders, innovators and change makers.

The LCT-RN is a nationwide network of researchers, practitioners, families, youth, and community representatives dedicated to improving the health of people across the life course.

About the Network

The Life Course Translational Research Network (LCT-RN), funded by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau within the Health Resources and Services Administration aims to bridge the gap between scientific knowledge and population health impact by applying new knowledge from life course research to long-standing public health problems through new types of partnership with families, communities, and other stakeholders.

With a focus on equity and creative co-design, the LCT-RN seeks to optimize life course health trajectories for children and families by strategically integrating—rather than merely aggregating— the knowledge, skills, tools, and expertise that research scientists, methodologists, practitioners, patients, family members, community residents, and other stakeholders and participants can provide.

Research Nodes and Cores

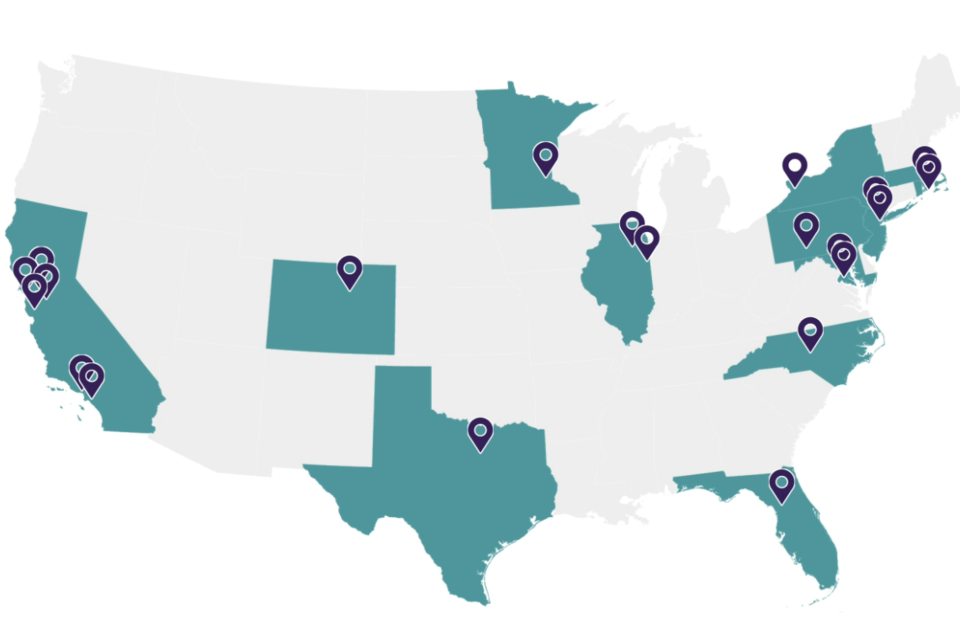

The Network’s 7 research nodes and 3 research cores are comprised of 125+ researchers from 40+ institutions from across the nation. These nodes partner with communities to co-design, test, implement, spread, and scale effective interventions that can improve life course health trajectories of children and families.

ADHD

ADHD Node

Adversity

Adversity Node

Early Childhood

Early Childhood Node

Engagement

Engagement Core

Equity

Equity Core

Family

Family Node

Measurement

Measurement Core

Maternal Health

Maternal Health Node

News from the Network

More LCT-RN News

Introducing the Life Course Translational Research Network (LCT-RN)

The Life Course Intervention Research Network (LCIRN) is now the Life Course Translational Research Network (LCT-RN)

Join the Network

Sign Up

Acknowledgement

This project is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under award U9DMC49250, the Life Course Translational Research Network. The information, content, and/or conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS, or the US Government.